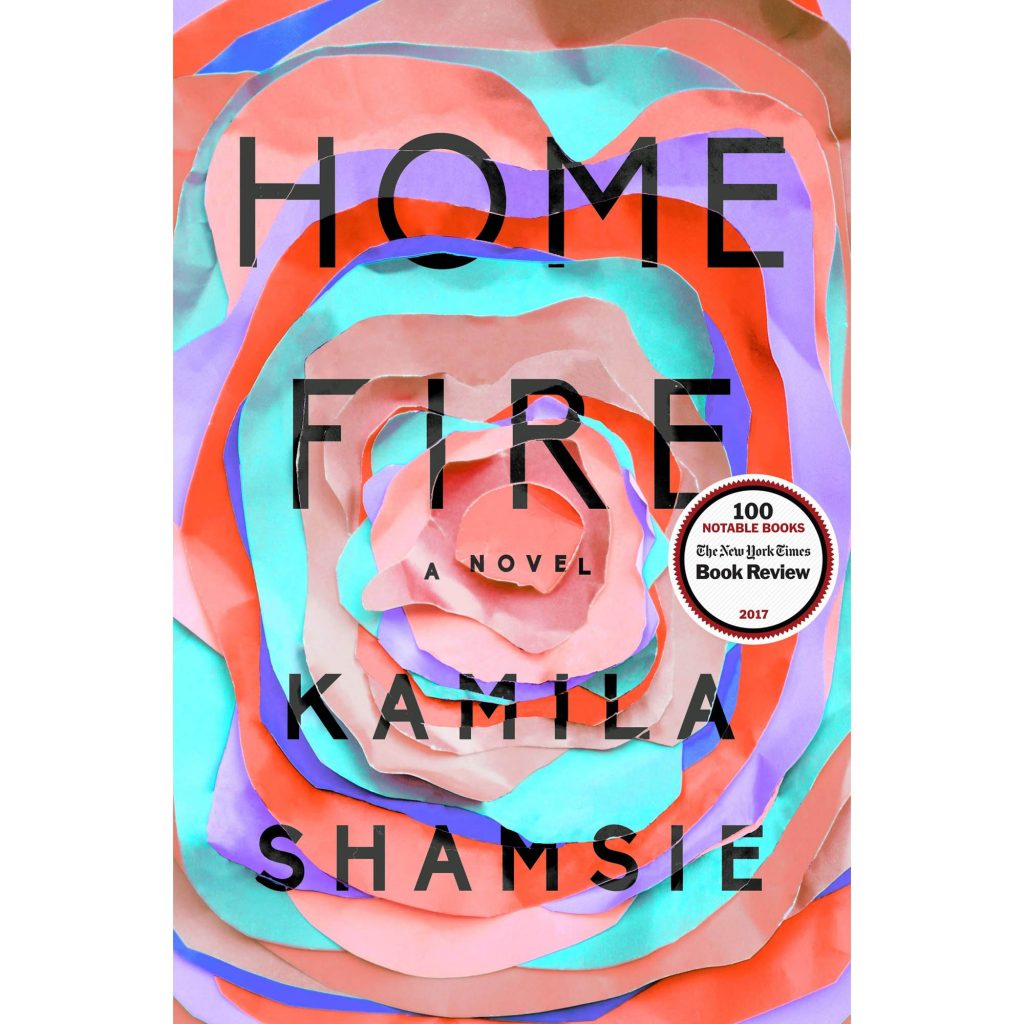

Haunting, hopeful and heartbreaking, Kamila Shamsie’s seventh novel, Home Fire is a bold and brilliant reimagining of Sophocles’ Antigone in the context of present day socio-political dilemmas as the personal and the political, faith and fanaticism, religion and relationships collide in a mesmerizing whirlpool of conflicting loyalties and love.

Haunting, hopeful and heartbreaking, Kamila Shamsie’s seventh novel, Home Fire is a bold and brilliant reimagining of Sophocles’ Antigone in the context of present day socio-political dilemmas as the personal and the political, faith and fanaticism, religion and relationships collide in a mesmerizing whirlpool of conflicting loyalties and love.

Ismene as Isma, Antigone as Aneeka, Polynices as Parvaiz and Antigone’s uncle Leon as the powerful politician Karamat Lone, the philosophical debate in Athens pitting natural law versus man-made law is as relevant today as it was at the time the original Greek tragedy was penned in which the distraught sister buries her brother in defiance of the command of the king.

Born and living in Wembley, the three Pasha siblings, Isma and the nine years younger twins Aneeka and Parvaiz, who she raised like her own children after the deaths of their mother and grandmother, have grown up with personal tragedies shadowing – and sometimes overshadowing – them as much as the political and religious connotations of being Muslims in a world divided over fundamentalism, terrorism, religious duty, religious intolerance and growing Islamophobia. Their father, a jihadist, who died being transferred to Guantanamo, remains an unspoken but not forgotten ghost in their lives and sets the prelude for the way the lives of his children pan out.

The novel begins with Isma being interrogated at Heathrow while on her way to Amherst, Massachusetts where she has a scholarship in a PhD program in Sociology. The opening line “Isma was going to miss her flight”, stated so simply and matter of factly, is in chilling contrast to the claustrophobia and humiliation of being questioned, searched and provoked while remaining composed and unruffled. Recalling her practice sessions of interrogation responses with her sister, a law student in London who would have been anything but calm under this scrutiny of racial profiling, Isma muses about Aneeka that she “knew everything about her rights and nothing about the fragility of her place in the world”. This is the crux of the novel, this tender, touching exploration of Aneeka’s intense vulnerability and naiveté, a contrast to her fierce determination and devoted passions. This devotion finds root most in her twin, her other half, who she loves uncritically and boundlessly. Parvaiz, conflicted and directionless, sheltered and shielded by his sisters’ love, achievements and hard work, helping out at the local library and “never seen without his headphones and a mic” but without any purpose in life, becomes an easy target for recruitment by the cunning and cruel Farooq. Assuming the role of father figure and mentor to the young boy, he plays on Parvaiz’s tortured ruminations on his father to glorify Adil Pasha as the brave, beloved warrior who was wronged and vilified by the Americans and whose son must now join the noble and religious Isil – wrongly portrayed by the west to be a terrorist organization – in order to not just avenge his father but also reclaim the glory and camaraderie of the Muslim brotherhood- a mirage of lies and deception which breaks soon after Perviaz arrives in Syria and is too deep in the quagmire to get out alive. Loyal to the core, Aneeka feels more hurt that he left without informing her than angry at what he did while Isma is shaken but furious at the selfish stupidity of her brother who has jeopardized all of their lives and futures.

Meanwhile, in Massachusetts, Isma encounters Eamonn the son of a Pakistani politician Karamat Lone and his Irish wife. Formerly a family friend, Lone, the opportunistic and power hungry Creon of the novel, is now despised and derided for not just renouncing his religion but also urging other Muslims to embrace inclusivity and ridiculing their backwardness.

A master of contouring her characters with the many shades and nuances which encompass them, Shamsie paints Isma with brutal candour, the self-sacrificing sister who raised her siblings, the dutiful woman who betrays her brother to protect herself and her sister, the giddy girl who feels a compelling attraction to the handsome, charming Eamonn. However, it is Aneeka who Eamonn falls in love with when he visits their home in London to deliver a package from Isma, it is Aneeka who needed this love from the Home Secretary’s son to save the one she loves the most. A passionate love affair, not entirely altruistic, forms the background of the story as the three siblings endeavour to pick up the pieces of their lives and salvage what they can of themselves and of each other.

Just like the bad guy in Antigone did not get a funeral while the good one did, Pervaiz encompasses both characters, the good and the bad, the perpetrator and the victim, the guilty and the wronged, and the question of his burial is what sustains Aneeka in a desperate bid to save her brother in death as she could not in life.

Otherwise restrained in its expression while the story does the talking, Shamsie occasionally employs dramatic language as Aneeka says to Eamonn about their love and her need for him to help save her brother “the world was dark and there you were blazing with light. How can you fail to love hope?” But more often, it is the characters who stand out more than the dialogues. The ruthless power and brutal candor of Lone is depicted with stunning subtlety while Eamonn, looked at as a good for nothing and a fool by his parents, a puppet by Aneeka and a drifter by most, emerges with principles and feelings too real to have been manipulated and too strong to falter in the face of all danger.

While exploring religion, morals, extremist and racism, Home Fire blasts questions which the readers must ponder over long after the last page has been turned and burns with a hope as fierce and unwavering as Aneeka is in her refusal to give up her vigil over her brother and Eamonn is in his refusal to give up Aneeka or disbelieve in their love, all accompanied dutifully with losses too devastating to enumerate.

Layered with symbols and richly interspersed with both tragedy and triumph, this novel grapples with the dilemma of society, family and religion, the troubles of intolerance and bigotry and the battle – and difference – between law and justice. This novel is not just thought provoking and interesting, it is also infinitely relatable, appealing to and calling out the baser impulses which lurk beneath our smiling exteriors. A page turner and pulsing with feeling, Home Fire is a timely and touching tribute to Antigone as well as the many misguided youth lured by false dreams in a moment of weakness and a life of yearning to belong – a longing to be at home.