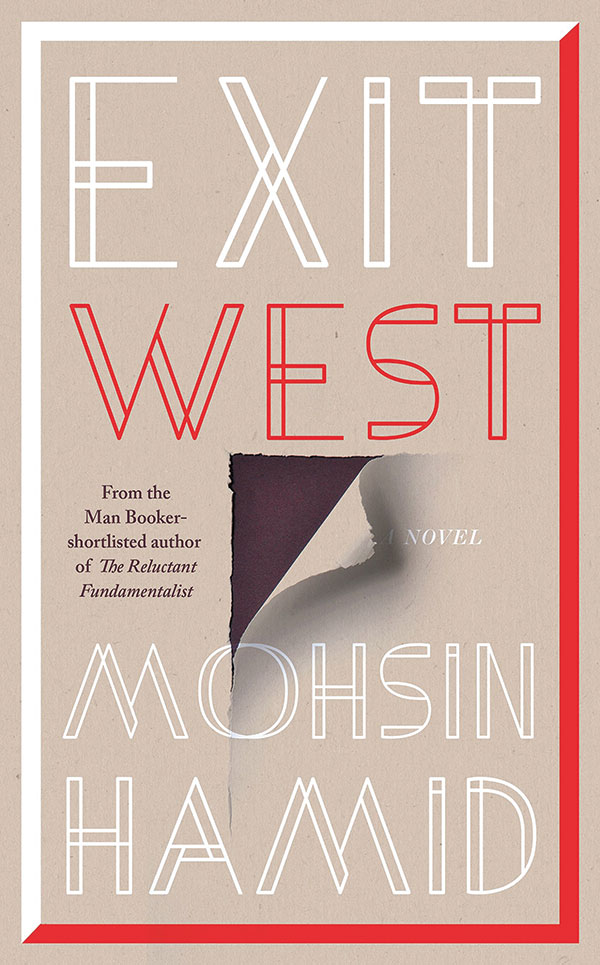

In a Skype interview with The New York Times, following the release of his fourth book, Mohsin Hamid mentions how he had never imagined four years ago, when he began writing this book, on noting the global migratory patterns following war-torn regions in the Middle East, that it would be so “grimly prescient” in the day and time that it was released. But that is exactly what happened. In fact, it was released within the first 100 days of a new president taking office in the United States, one who swiftly imposed stringent measures on the migration of refugees and on the entrance and sustainability of illegal immigrants from very specific nations and countries. Over the last few years, even the most perfunctory perusal of news headlines has wrought reports and op-eds of Europe’s closed borders, drownings in the Mediterranean, scuffings, tear gas and barbed wire at patrolled borders, the heightened use of Google maps for long treks on foot, refugee camps and so on. As these headlines and stories make their way into our consciousness and vernacular, one wonders, wrought, if there is anything that can be done about it. Simply hoping that all these stories work out is wishful thinking. But that in fact is exactly the premise of Hamid’s new book, Exit West, a story based on the refugee crisis but with porous borders. What he does though through an element of magical realism, is take the trek out of the plot, creating instead, magic doors that lead to different countries and cities, negating the need for perilous journeys by foot, train or air, though all other dangers associated with camps, and being new migrants in strange lands, remain. Telling the story of a young couple stuck in an unnamed but familiar, war-torn city, where they do not remain safe from militants and bombs anymore, find a passage out, through a smuggler, exiting through a door, arriving instead at the Greek island of Mykonos, at a makeshift refugee camp. From thereon they find their way to London, arriving at an opulent mansion in Kensington, joined later by more than 50 other migrant families, all arriving via different doors in the mansion, only to be removed by police not the owners. He exposes the makings of the phenomena we now know as Brexit, the exit of a superpower from its European counterpart on grounds of concern and disconcert of the citizens of Britain and at the influx of refugees threatening the safety and stability of their social and political structures, throwing their own proliferation at globalisation into a spin. As Saeed and Nadia navigate migrant life in London, the eventual bombing of makeshift refugee camps, and the rebuilding of their own communities within the small states the migrants have created for themselves, Hamid takes us into the inner consciousness and psyches of the two main characters, as they make their way out of their native countries and into foreign ones.

During his press tour through New York, Hamid made an appearance on Late Night with Seth Myers, to speak about what encouraged him to write on this topic. He responded how he was more encouraged about the stories that precede migration, precisely, “…What leads someone to leave where they live. What’s the enormous sorrow or pain, and then what happens when you get there, which is most of your life?”

In writing a story of migrants while tracing their migratory routes, he also comments on several other socio-political factors that one may not otherwise have thought of. As he probes the consciousness deeply, by internally revealing characters’ nuances and behavior, he also explores the phenomena of memory and nostalgia. Of belonging and belongings and the roles they play in our everyday lives. As dozens of migrant families take up a single Kensington mansion, he notes how they are vacation homes for the affluent, remaining vacated for several months a year, a rebuke no doubt on the unwillingness of the city of London to house external communities.

“The news in those days was full of war and migrants and nativists, and it was full of fracturing too, of regions pulling away from nations, and cities pulling away from hinterlands, and it seemed that as everyone was coming together everyone was also moving apart.”

–Mohsin Hamid, Exit West

His poetic prose runs consistent throughout – long run-in sentences that are his trademark style, punctuated by characters’ inner thoughts. In doing so, he creates a psychological study of people in flux. We experience their struggles, their courage and their fears. We feel viscerally what they feel, and what they hope to grow and be. Hamid concentrating on not just one ethnicity but several, creates an underworld of sorts. An alternate parallel universe belonging to just migrant communities and their families, who exist as “the other” amongst “nativists”, in different cities and countries where we are forced to exist in that world with them, as they carry us through their doors.

Nadia and Saeed, on having come full circle in London, learning of a way forward and how to pave it, become involved in the physical creation of a new community of housing that will be their new home. On tiring of it, and noting a change in their own relationship, find a new door, one leading to California, where they want to take their newfound roles and pursue them further, the question of returning to their hometowns long unimaginable. As the book begins to reach its final chapters, Marin, San Francisco becomes the final destination of the two, and for Hamid also to make his final point. As he spends the book examining not only the plight of people in flux, but also those geographical boundaries that house them, however temporarily, we begin to wonder about the idea of a nation state, and how those boundaries define or become definitive of an adjunct influx or exodus of a group of people. The point he specifically makes about this city is that of a variety of different groups of people and the ebb and flow they bring to that city’s culture, the music, food etc, noting the strength of a city and community derived from those of various ethnic backgrounds.

The story ends in San Francisco, on a note that is quite open-ended much like the fate of the world’s displaced persons, unwritten and unsure.

![]()

TEXT: FAIZA VIRANI

PHOTOGRAPH: GETTY