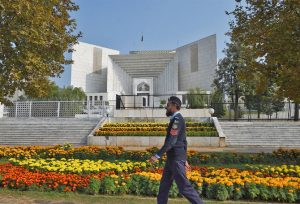

The appointment of judges to the Supreme Court controlled the judiciary.

The attention also remained on the events surrounding the change of regime.

ISLAMABAD: The conflict over the Supreme Court’s judicial appointments as well as the circumstances surrounding the regime change continued to dominate the judiciary in 2022.

On February 1, Justice Umar Ata Bandial took the oath necessary to become Pakistan’s chief justice (CJP).

Developing an agreement over the appointment of judges was his major obstacle.

Last year, five SC judges announced their retirement.

CJP Bandial was unable to reach an agreement, however, since the Judicial Commission of Pakistan (JCP), a body mandated by the Constitution to nominate judges for the higher courts, was divided over the promotion of high court justices to the Supreme Court.

A portion of the JCP, including the superior bars, insisted that when selecting SC judges, the seniority principle be respected.

The other portion, headed by CJP Bandial, prioritised other factors, such as merit and capability, while deciding which judges would be elevated to the SC.

Because of this impasse, there are still just two judges on the Supreme Court.

On July 28, the four candidates put out by the CJP for elevation to the SC were rejected by the majority of the JCP members.

Later, CJP Bandial made the audio recording of the JCP proceeding public, in which it was clear that senior SC judges were at odds with one another.

SC Senior Puisne Judge Justice Qazi Faez Isa, a JCP member, objected to the selection procedure for justices of the supreme court in a number of letters to the CJP.

The JCP, with the support of the majority of its members, authorised the elevation of three judges to the SC on October 24 after nine months of impasse.

Athar Minallah, the Chief Justice of the Islamabad High Court, and two younger high court judges were among them.

The law minister and Pakistan’s attorney general, who represent the two federal government members in the JCP, also supported these nominees.

It was observed that as a result of the junior justices’ elevation to the SC, the situation at the Sindh High Court deteriorated.

Senior SHC judges who were passed up for appointment to the top court felt let down.

The SC also had a significant impact on the April regime shift.

The Supreme Court, which is chaired by CJP Bandial, heard a plea from the Supreme Court Bar Association (SCBA) asking for the conclusion of the procedure for a motion of no-confidence against the previous prime minister, Imran Khan, in accordance with Article 95 of the Constitution.

When the no-trust resolution against Imran was rejected by Qasim Suri, the deputy speaker of the National Assembly at the time, the supreme court started suo motu proceedings and nullified his decision.

The court then ordered the NA speaker to finish the no-confidence motion process.

The SC and IHC were both opened late at night, when the NA speaker was causing delays.

The PTI leadership, however, harshly criticised these judges for holding evening court sessions.

In response to this complaint, the SC has stated its position about the application and interpretation of Article 63(A) of the Constitution.

The vote of a defection-committing politician in breach of Article 63 (A) could not be counted, according to the same bigger bench, which had ruled with a majority of three to two.

The majority of attorneys vehemently disagreed with this view, arguing that it amounted to “re-writing” the Constitution.

Even experienced attorneys referred to it as the worst decision of 2022.

Likewise, the SC heard the plea of the outgoing chief minister, Parvez Elahi, at its Lahore Registry late at night after deputy speaker of the Punjab Assembly Dost Muhammad Mazari had rejected 10 PML-Q votes during the election for the new chief minister.

Representatives of the SCBA and the PML-N-led coalition government asked the SC to convene a full court to hear the dispute.

A special court headed by CJP Bandial and consisting of Justices Ijazul Ahsan and Munib Akhtar, however, rejected their appeal.

The federal respondents all made the decision to abstain from the court proceedings.

The judiciary suffered shame as a result of this.

The SC subsequently ruled that it was unlawful for the deputy speaker to disallow the votes of 10 PML-Q MPAs.

Elahi, the petitioner, was also named the new chief minister of Punjab by the court.

Senior attorneys argued that although the decision was correct, a bigger bench should have made it.

Following the regime transition, the PTI filed a number of constitutional petitions on a variety of topics, such as changes to the National Accountability Ordinance (NAO), the right to vote for Pakistanis living abroad, the surveillance of senior government officials, etc.

These issues are still open for debate.

An SC panel led by Justice Ijazul Ahsan intervened after the federal government refused to allow the PTI to organise a sit-in at Islamabad’s D-Chowk.

He gave the federal government officials instructions to find the PTI an other location for a rally in the nation’s capital.

When PTI leaders and activists arrived at D-Chowk, they nonetheless broke the May 25 order.

The interior ministry filed a request to start a contempt case against the PTI leader.

Four members of the larger bench were unable to locate sufficient evidence to issue a contempt notice to Imran, therefore the case is still pending.

The SC also took suo motu notice of the alleged executive intervention in the prosecution and investigation of high-profile corruption cases involving top government officials. This issue is still open.

The Reko Diq project deal was deemed legitimate by the top court.

The court also overturned Faisal Vawda’s lifetime ban from holding public office.

Due to his dual citizenship at the time of the 2018 general elections, Vawda was disqualified.

The PTI leadership frequently criticises the supreme court for failing to uphold the “basic rights” of citizens in cases where the interests of the wealthy were at stake.

Similarly, several parliamentarians and human rights advocates are questioning why MNA Ali Wazir has not been released as of yet.

They are also perplexed as to why the SC did not intervene to “rescue” PTI Senator Azam Swati, who was a victim of the State and had his privacy invaded.

The alleged mistreatment of PTI leader Shahbaz Gill in custody also received no suo motu action.

In addition, the SC rejected the PTI leader’s request that a FIR be registered in connection with the attack on him in Wazirabad, Punjab, as he had requested.

CJP Bandial has, nevertheless, taken spontaneous notice of the murder of journalist Arshad Sharif in Kenya.

To look into the matter, a special joint investigation team (JIT) has been established. The SC will start hearing the case in the first week of January with a larger bench.

The SC, headed by CJP Bandial, continued to be effective in lowering the number of open cases last year despite not having its full complement of judges.

During CJP Bandial’s tenure, a discipline is being seen in the arrangement of the benches as well as the fixing of cases.

The number of open cases had decreased by 2,653 by the end of the autumn of 2022, according to a statement from the SC.

Former extra attorney general Tariq Mahmood Khokhar made a comment about the performance of the supreme court in 2022 and claimed that not all judges agreed with the CJP’s methods.

They were angry about the lack of full court sessions, the setup of benches, the de facto exclusion of senior judges from high-profile cases, and the appointment of SC judges in violation of the seniority principle, he continued.

The supreme court will have many difficulties in the coming year.

To guarantee greater transparency about judge selections, bench makeup, case fixation, etc., the CJP’s discretionary powers must be regulated.

For the past three years, there have been no full court proceedings.

Appointments to the supreme court should be based on consensus.

It must be put a stop to the idea that judges with the majority of similar viewpoints are included in larger or special benches to hear high-profile cases.

The SC judges should also dispel the notion that they were swayed by “powerful circles” in controversial or political cases.