Who is China’s President Xi Jinping, dubbed the “most powerful leader after Mao Zedong”?

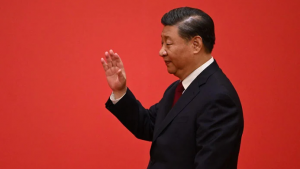

On October 23, 2022, China’s President Xi Jinping gestures to the media as he enters the Great Hall of the People in Beijing with members of the new Politburo Standing Committee of the Chinese Communist Party, the country’s top decision-making body. — AFP

On October 23, 2022, President Xi Jinping of China gestures to the media as he enters the Great Hall of the People in Beijing with members of the new Politburo Standing Committee of the Chinese Communist Party, the government’s top decision-making body. — AFP

Based on his understated demeanor, his family history, and possibly some misplaced optimism, some observers believed Xi Jinping would be the most liberal Communist Party leader in China’s history when he assumed power in 2012.

Ten years later, those predictions are in ruins, demonstrating how little was known about the man who, following his historic election to a new five-year term on Sunday, is now China’s most powerful leader since Mao Zedong.

Xi has proven to be ruthless in his ambition, intolerant of opposition, and driven by a hunger for power that permeates nearly every facet of contemporary Chinese life.

In place of being mostly recognized as the spouse of a famous singer, he has developed a personality cult unseen since Mao’s time thanks to his apparent charisma and skill as a political storyteller.

In official party legend, the vivid facts of his early life have been rinsed and repackaged, but the man himself — and what motivates him — remain slightly more mysterious.

According to Alfred L. Chan, the author of a book about Xi’s biography, “I reject the popular assumption that Xi Jinping struggles for power for power’s sake.”

“I would propose that he pursues power as a tool… to realize his goal.”

Despite foreign media investigations revealing his family’s accumulated fortune, another biographer, Adrian Geiges, told AFP that he did not believe Xi was driven by a desire for personal enrichment.

Geiges remarked, “That’s not his interest.”

He genuinely believes that China can become the most powerful nation in the world.

The Communist Party’s function is crucial to that vision, which Xi refers to as the “Chinese Dream” or “great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation” (CCP).

Kerry Brown, the author of “Xi: A Study in Power,” stated that “Xi is a man of faith… for him, God is the Communist Party.”

“Not taking this faith seriously is the biggest error the rest of the world makes about Xi.”

On October 22, 2022, China’s President Xi Jinping attends the 20th Chinese Communist Party Congress’s closing ceremony at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing.

On October 22, 2022, China’s President Xi Jinping attends the 20th Chinese Communist Party Congress’s closing ceremony at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing.

Though he was raised as a “princeling,” or a member of the party elite, “traumatized” Xi may not appear like an obvious fit to become a CCP zealot.

According to the elder Xi’s biographer Joseph Torigian, his father, Xi Zhongxun, was a revolutionary hero turned vice premier whose “strictness toward his family members was so serious that even those close to him feared it bordered on the inhuman.”

But Chan claimed that “(Xi Jinping) and his family) were traumatized” by Mao’s purge of Xi Zhongxun and his targeting during the Cultural Revolution.

Overnight, his status changed, and the family was divided. According to reports, one of his half-sisters committed suicide as a result of the harassment.

According to Xi, he was shunned by his peers; political scientist David Shambaugh theorizes that this experience helped him develop a “feeling of emotional and psychological separation and his autonomy from a very young age.”

Xi was sent to the countryside of central China when he was just 15 years old, where he spent years transporting grain and staying in cave houses.

He subsequently remarked, “The severity of the labor astonished me.

In “struggle sessions,” he was also required to speak out against his father.

In a 1992 interview, he described the sessions to a Washington Post reporter “with a trace of anger,” adding, “Even if you don’t understand, you are forced to comprehend.”

It accelerates your maturation.

His childhood traumas had given him “toughness,” according to his biographer Chan.

“He frequently takes risks. When tackling issues, he frequently approaches them with two hands. But he also recognizes the arbitrary nature of authority, which is why he emphasizes law-based governance.”

systematic, discrete

The cave that Xi slept in is now a popular domestic tourist destination, emphasizing qualities like his care for China’s poorest citizens.

One local described an almost legendary person who studied books in between pauses from laborious work when AFP visited in 2016 “so one could see he was no common man.”

But it doesn’t appear that was clear at the time. When he first arrived, according to Xi, he wasn’t even considered “as high as the women.”

Due to the stigma associated with his family, his application for CCP membership was first turned down many times before being approved.

After becoming the party chairman of a hamlet in 1974, Xi rose to become the governor of the Fujian province on the coast in 1999, the party chief of Zhejiang province in 2002, and finally the mayor of Shanghai in 2007.

According to biographer Geiges, “He was working very methodically… to obtain experience by starting at a very basic level, in a village, then in a prefecture… and so on.”

He was also quite clever by maintaining a low profile.

After Mao’s death in the late 1970s, Xi’s father was given a second chance, which greatly improved his son’s standing.

After divorcing his first spouse, Xi wed the famed singer Peng Liyuan in 1987. At the time, she was far more well-known than he was.

Even so, as evidenced by remarks made by his host during a visit to the United States in 1985, not everyone recognized his potential.

Eleanor Dvorchak was cited as remarking, “No one in their right mind would ever suppose the guy who stayed in my house would become the president,” in a subsequent issue of the New Yorker magazine.

Former senior CCP cadre Cai Xia thinks Xi “suffers from an inferiority complex, knowing that he is inadequately educated in comparison with other top CCP leaders,” according to exile in the US.

He is thus “thin-skinned, inflexible, and dictatorial,” she claimed in a recent Foreign Affairs essay.

As the “Heir of the Revolution,”

Chan, however, noted that Xi has always seen himself “as an heir of the revolution.”

He was elected in 2007 to the Politburo Standing Committee, the top decision-making body of the party.

There wasn’t anything in Xi’s administrative experience that predicted his behavior once he became the leader five years after Hu Jintao was ousted.

In contrast to his predecessor, he has actively supported a far more muscular foreign policy and has cracked down on civil society organizations, independent media, and academic freedoms. He has also allegedly presided over human rights violations in the northwest Xinjiang province.

Scholars are forced to look through Xi’s prior papers and speeches in order to deduce his objectives because they don’t have access to him or anybody else in his close circle.

From Xi’s first recorded utterances, Brown noted, “it is clear that the party’s objective to build China a great country again” is of the utmost importance.

In order to increase his own and the party’s popularity among the populace, Xi has successfully harnessed the narrative of a rising China.

But there is also an indication that he worries his hold on power may weaken.

Geiges echoed this sentiment, saying, “The demise of the Soviet Union and of socialism in eastern Europe was a great shock.” Xi attributes the collapse to the Soviet Union’s political opening up.

Therefore, he made the decision that something similar should not occur in China. As a result, he wants the Communist Party to be led by a strong individual.